Written by Jacob Tetteh, PhD Candidate

Introduction

The intake of potable drinking water is needed for the sustenance of all human life and existence, however, in 2020, 771 million people globally lacked even the basic drinking water service according to the WHO and UNICEF. In fact, the World Economic Forum in January 2021 reports that the water crisis is the fifth global risk in terms of its potential negative effects on society. In sub-Saharan Africa, the situation remains crucial in that nearly half of the people without the basic drinking water service reside here.

As a result, the drinking water landscape in sub-Saharan Africa remain highly heterogeneous. For instance, in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA) – the largest urban agglomeration in Ghana, these diverse drinking water sources range from the most common packaged water sources such as sachet and bottled water to piped sources among others. In this region, increasing urbanization is severely compromising urban access to clean water. Also, in this environment, the informal and private sector have played a vital role in expanding drinking water services beyond centralized water systems especially in unregulated housing areas in order to keep up with urbanization. This suggests that in order to have flexibility and everyday affordability, residents are usually compelled to use a variety of water sources. In view of this, there was the need to know the actual water consumption pattern over space and time in GAMA using citizen-science (volunteer) based data collection approaches.

Drink Smart App Roll-out

To achieve this aim, we rolled out a drinking water source application software called the “Drink Smart” in November of 2022 to be used by interested participants for a period of two to three weeks. Consequently, I was part of a joint Imperial College London and University of Ghana research team that visited 7 communities across the different socio-economic divide in GAMA to undertake this roll-out. These communities were Community 18, Kpone, Teshie, Gbegbeyisee, Old Fadama, McCarthy Hill and Tomefa. The Drink Smart app was built for both Android and IOS platforms in order to allow for wide range of users and its development was led by Dr. Laure Sioné at Imperial College London. Before the roll-out, initial engagements with the assembly members and opinion leaders of these communities were done to ascertain the field visitation dates and times. Second, while in the field, we engaged participants in both English and the local languages spoken by the residents of these localities (Picture (a)). Here, interested residents above 18 years of age who owned an Android or IOS phone and could connect to the internet at regular times were allowed to participate freely.

Picture (a): Engaging with some residents at Kpone during the Drink Smart App Roll-out

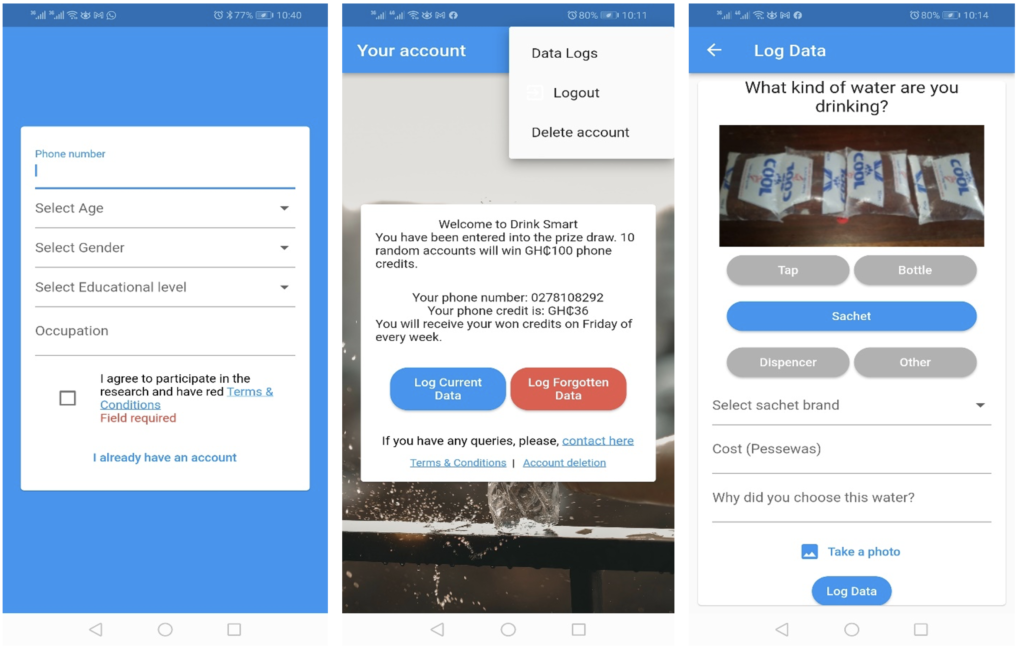

During the roll-out sections, participants undertook a number of steps. After downloading the app, they were initially registered to pave the way for login. Once the app was set up and running, the main app interface offered the flexibility of logging current or forgotten data. Participants were also allowed to discontinue and delete their account at will. Further, once a participant selected the “log current data” button, they were asked “What kind of water are you drinking?”. The options included tap water, sachet or bottled water, dispensers and others. It was also possible to log other information, for instance, if a participant selected sachet water they could then include the brand, the cost and the reason behind the choice of that brand of sachet water. With respect to the less popular brands of sachet water sources, participants were given the option to upload a photograph of the label (Pictures (b)).

Pictures (b): App registration interface (left); participant’s account interface (middle) and log data interface (right)

A Successful App Launch and a Few Lessons Learned

The roll-out of the Drink Smart app was very successful overall, with 3084 data points logged over 2 weeks by 179 participants. Users received phone credits to recompense them if they exceeded a minimum level of data entries using the app. One question which was often asked by residents in almost all of the communities visited was “how would this research benefit me?” In an attempt to answer this question, participants were made to understand that the app could help them log their own water consumption patterns and choices. Also, the app could help them know and track the changes in their water consumption at home or elsewhere, the cost involved and the brands they patronize. The app itself was pre-programmed to give notifications at certain times of the day, to remind the participants to log data. However, users thought the app should have been designed to give them the flexibility in setting their own reminders at regular times to help them to remember to hydrate and record that afterwards like some other drinking water application softwares.